I’ve been thinking for a couple of weeks now about W. P. Kinsella’s wonderful baseball novel Shoeless Joe, with its subplot involving protagonist Ray Kinsella persuading notoriously reclusive author J. D. Salinger to accompany him on his whimsical journey to, ultimately, northern Minnesota in search of baseball footnote Archibald “Moonlight” Graham. “Are you kidnapping me?” Salinger asks Ray, who has cornered “Jerry” in the driveway of his secluded home in Windsor, Vermont:

I’ve been thinking for a couple of weeks now about W. P. Kinsella’s wonderful baseball novel Shoeless Joe, with its subplot involving protagonist Ray Kinsella persuading notoriously reclusive author J. D. Salinger to accompany him on his whimsical journey to, ultimately, northern Minnesota in search of baseball footnote Archibald “Moonlight” Graham. “Are you kidnapping me?” Salinger asks Ray, who has cornered “Jerry” in the driveway of his secluded home in Windsor, Vermont:“Oh, please, that’s such an awful word. I’m sorry. I planned things so differently. I wanted to convince you to come with me. I never wanted to have to do this . . .”In Field of Dreams, the disappointingly diluted movie version of the novel, the Salinger figure is replaced by a character named Terence “Terry” Mann, played by James Earl Jones (who in my estimation is always really just playing James Earl Jones—yawn . . .). Lamely-conceived and lamely executed, this substitution was prompted (or so I understand) by the fear—or the threat—that visually representing the intensely private Salinger on the big screen would result in a lawsuit that verbally representing him in the pages of the novel could not.

00“Then you are.”

00“I just want to take you for a drive. I have tickets for a baseball game. A baseball game,” I say again. . . .

00“And if I don’t?” . . .

00What can I possibly say? I am inarticulate as a teenager at the end of a first date, standing in the glare of the porch light, a father hulking behind the curtains.

So . . . did I have in mind that scene, or scenario, from the novel when I headed off to Santa Fe a few weeks ago, having told various people that my purpose in going there was “to stalk Cormac McCarthy”? Well . . .

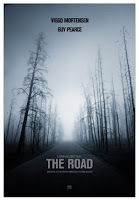

Well, McCarthy is in the headlines these days thanks to the release, just yesterday, of

the movie adaptation of his relentlessly bleak post-apocalyptic novel The Road. And part of the McCarthy story in newspapers and newsmagazines involves his Salinger-like reclusiveness, his retreating to the outskirts of Santa Fe where he hunkers down—or bunkers down in pre-apocalyptic fashion—far from the madd(en)ing crowd of paparazzi, autograph seekers, and other celebrity hounds. Well, it ain’t necessarily so; in fact, last week The Wall Street Journal published a very engaging interview—or extracts from a conversation—with McCarthy and film director John Hillcoat, conducted in San Antonio, thus giving the lie to McCarthy’s reputed utter reclusiveness. Anyway, I haven’t seen the film yet . . .

the movie adaptation of his relentlessly bleak post-apocalyptic novel The Road. And part of the McCarthy story in newspapers and newsmagazines involves his Salinger-like reclusiveness, his retreating to the outskirts of Santa Fe where he hunkers down—or bunkers down in pre-apocalyptic fashion—far from the madd(en)ing crowd of paparazzi, autograph seekers, and other celebrity hounds. Well, it ain’t necessarily so; in fact, last week The Wall Street Journal published a very engaging interview—or extracts from a conversation—with McCarthy and film director John Hillcoat, conducted in San Antonio, thus giving the lie to McCarthy’s reputed utter reclusiveness. Anyway, I haven’t seen the film yet . . .. . . but I have seen Cormac McCarthy.

I don’t want to give away too many specific details of my “sighting” him because I don’t want to detract from his right to privacy. I’ll just mention that whenever I travel, one of the ways I get my bearings in a new city or town is by mining the Yellow Pages for a list of used bookstores that becomes my connect-the-dots map of wherever I happen to be. In Sante Fe, I managed to get to only two of the stores on my list. In the first one, I had a great visit with the proprietor, Henry: we chatted about everything under the southwest sun . . . including how, as Henry put it, “Cormac will come in here and sit down and talk about anything and everything . . . except about being an author.” And he added: “And he won’t sign books.”

From that bookstore on North Guadalupe Street, I walked about ten minutes up through The Plaza (the heart of Santa Fe) to East Palace Street. Arriving at the bookshop there just before closing time, I had just begun to browse when I heard a voice talking with the proprietor and his assistant about “the Institute” (that is, the Santa Fe Institute, which I knew McCarthy is associated with). Could it be . . . ? I wondered, though I already knew the answer: I had recently re-watched Cormac McCarthy’s interview on Oprah . . . and the voice was unmistakably his. Just to be sure, I double-checked the physical person standing three feet away from me against the author photo in a copy of The Crossing that I pulled off a shelf . . .

So . . . did I pull a Ray Kinsella and try to kidnap him? I just want to take you for a drive . . .

No. I left him alone, though as soon as he left the shop, I confirmed with Nick and Pat, the proprietor and his assistant, that I had indeed had a close encounter with America’s second-most elusive and reclusive author. I returned to the shop the next day to browse some more and Pat told me “you played it just right”—had I “outed” McCarthy, he explained, I would have created a very awkward moment indeed! He also mentioned that McCarthy is not quite as reclusive as everyone believes: because no one expects to see him, he is actually able to “hide in plain sight” . . .

So did I really go to Sante Fe to stalk Cormac McCarthy? Of course not. I went there to scout out possible relocation destinations for the Witness Protection Program, should I ever be (un)lucky enough, on my travels, to bump into fugitive South Boston gangster Whitey Bulger, high on the roster of America’s Most Wanted. I used to see him out walking around Castle Island when I lived in Southie years ago. I think I’d recognize him anywhere . . . though I doubt that I’d find him in a used bookstore . . .